Journal of African Studies. 1978. Vol. 5, no.1, pp. 34-54

|

Students of British relations with West Africa are quite familiar with the impact of Buxtonianism, on both the formulation, and execution of official British policies 1. Buxtonianism as a philosophy derived its name, from the work and influence of Thomas Fowell Buxton, one of the leading British abolitionists, if not the leading one, during the second quarter of the nineteenth century. As successor to William Wilberforce in Parliament after his death, Buxton rose to prominence and became the spokesman for all abolitionists in England. He thus represented a group of people, and a tradition stretching back to the eighteenth century, whose hatred for the nefarious institutions of the African slave trade and slavery led them to agitate relentlessly under favorable and unfavorable circumstances. They brought about first the abolition of tha British slave trade in 1807 and other subsequent measures to reduce and eliminate the continuation of the illicit traffic by British and other nationalities. Their efforts culminated in the abolition of slavery 2 within the British Empire in 1833.

These measures, however, proved inadequate, and slavery and the slave trade continued to thrive with the active involvement of Spain, and nationals from the United States, France, Portugal, Brazil. The abolitionists, led by Buxton, were outraged by this, and Buxton personally marshalled facts to dramatize the frightening proportions of the slave trade. In his book The African Slave Trade and Its Remedy, published in 1840, Buxton estimated that more than 150,000 Africans were being taken away from Africa annually and sold as slaves in the New World, where the demand was great for cheap labor for the cultivation of profitable staples like sugar, cotton, tobacco, rice, coffee, or indigo 3.

The inadequacy of the measures taken was blamed on the policies of the British government. They were not considered to be vigorous enough. This, however, was not totally justified, since Britain had initiated some positive measures to counteract the continuation of te slave trade. Among these were the most dramatic measures of the establishment of the colony of Sierra Leone in 1787 as a settlement for emancipated slaves in Africa and a naval squadron in 1808 to patrol the waters along the stretch of the coast and capture ships supposed to be involved in the slave trade.

These measures were inadequate for a number of reasons. Not only was the number of ships in the squadron limited, but they could by law capture.only ships of British nationality. Since some other nations, for example, the United States, refused to sign joint treaties providing for mutual search and, seizure of slave ships ofn both nations, slave traders could conveniently show false papers and escape. Beyond that, the coastline was so long with so many inlets in which slave ships could hide and dodge the naval patrol that only a small proportion of slave ships were ever caught. They were prosecuted in several courts of Mixtes Commissions, for exemple at Freetown, and founde guilty and seized. Moreover, many Africans, compelled by economic, political, and social circumstances, were quite willing to sell slaves to the slave traders. It is not surprising therefore, that these measures were severely criticized by the abolitionists 4. Ironically, those who represented the slave-trading interests in England felt that Britain was doing too much already, and resisted all efforts to transform British policies radically in West Africa 5.”

The British government, however, could not deny the existence of the slave trade and was committed to its extinction. The problem was finding an adequate solution that would not add to colonial expenditures. During the 1820s and 30s, therefore British relations with West Africa were in a flux in the absence of a clear policy.

Fowell Buxton and the abolitionists came up with a policy, one which they were sure would eradicate slavery in West Africa specifically and Africa at large, and ultimately the slave trade. Buxton thus won prominence as the leading spokesman for the enunciation of such a policy in the 1830s. The policy in the main called for a more aggressive approach to terminating the slave trade in Africa, thereby undermining the transatlantic slave trade. Buxton and the abolitionists wanted the British government to sign treaties with, African chiefs that enjoined them from participating in the slave trade. In case of violations the navy should be able to move in and apprehend violators, particularly European 6.

This policy was likely to succeed if the roots of slavery in Africa were attacked. The prescription for achieving this was the active encouragement of “legitimate commerce,” that is, the cultivation and sale of such products as cotton, groundnuts, or palm oil instead of raiding for prisoners of war to be sold as slaves. African labor would thus find employment in the new scheme of things, and trans. port of slaves to the new world would certainly diminish.

This projected transformation of the economic relations between Britain and Africa would redound to their mutual material advantkae, while at the same time serving to eradicate a centuriesold inhuman scourge. During this era Britain certainly needed raw materials from Africa, and under Buxton's program they would be provided in return for manufactured goods. Buxton himself summarized the position extremely well.

Africa and Great Britain stand in this relation toward each other. Each possesses what the other requires, and each requires what the other possesses. Great Britain wants raw material[s], and a market for her manufactured good[s]. Africa wants manufactured good[s] and a market for her raw materials. Should it, however, appear that in place of profit, loss were to be looked for and obloquy instead of honour. I yet believe that there is that commiseration, and that conscience, in the public mind, Which will induce this country to undertake, and with the Divine blessing, enable her to succeed in crushing “the greatest practical evil that ever afflicted mankind. 7”

Befitting a Victorian gentleman, Buxton further elaborated his policy to include the spread of the gospel with its attendant beneficial effects among the African peoples. He noted, “Africa still lies in her blood. She wants our missionaries, our schoolmasters, our bibles, all the machinery we possess, for ameliorating her wretched condition 8.” This, then, represented the abolitionists program summarized as the “Bible and plough” policy.

The program of the abolitionists was necessarily opposed by the West India interests in England. Buxtonianism had an appeal, however, and was eventually able to win support from the British government for a practical test of its program in Africa 9. As can be seen from the brief elaboration of Buxton's program above, it combined both vision and reality. It did not appeal merely to so-called high moral virtues, but also to concrete economic interests. In effect, it combined Victorian humanitarism and keen self-interest, which altbough seemingly paradoxical, were perfectly understood and acceptable to Victorian England. Thus the ultimate support that Fowell Buxton and his followers won for their schemes in Africa was not visionary and anchored in self-delusion. Buxtonianism won support precisely because its success would be to the material advantage of England 10.

While the implementation of Buxton's program in Africa has been dealt with by historians, most scholars have regarded the 1841 Niger Expedition as the sole experiment of Buxtonianism. Without doubt, it was the most publicized, and if it had succeeded, it could have radically altered British relations with West Africa. This, however, is no excuse for the almost total neglect of a Buxtonian experiment in Sierra Leone, the 1841 Timbo Expedition, which started from Sierra Lone. This neglect becomes all the more serious if it is remembered how pivotal Sierra Leone was in the debates between West Indian interest and antislavery groups in England during the nineteenth century. This article addresses itself to the Timbo Expedition to remedy this neglect. It will further examine the expedi. tion in the light of the influence of Buxtonian ideas in its planning and execution.

Sierra Leone itself was an experiment that reflected the hopes of British abolitionists 11. A settlement (the Province of Freetown), which in 1808 became a British colony, was established in 1787 on an area of about twenty square miles on a peninsula close to the River Sierra Leone or Rokel with about 400 ex-slaves (the Black Poor) from England. Its early history was fraught with innumerable difficulties, ranging from the unwillingness of the settlers to farm, understandable because of the poor soil, and the hostility of the neighboring indigenous peoples, the Temne for example, which resulted in several attacks on the fragile settlement to the persistence of the slave trade in its vicinity. With the assistance of philanthropists like Granville Sharp, and able and dedicated British administrators like Governor Clarkson, the settlement managed to survive. But probably the most significant impetus for survival resulted from the arrival of over 1,000 colonists of African descent from Nova Scotia in 1792 and a further 600 Maroons from Jamaica in 1800 following their compromise with the British colonial authorities there. When the settlement became a colony in 1808 and the center of British abolitionist efforts in West Africa, it was also diosen as a suitable refuge for African slaves freed from slavers on dw Atlantic. The consequence was the addition of thousands of liberated Africans to the colony, which by 1840 had a total population of over 60,000 12. These circumstances gave a vitality and sigAficance to the colony that it could not have anticipated at its founding.

As an experiment, however, Sierra Leone represented far more than a settlement of ex-slaves, at least in the reckoning of the abolitionists. Sierra Leone was envisaged as a demonstration of the humanity of the African, who under the guiding spirit of civilization, most naturally in this case British civilization, would himself evolve into a civilized being. The colony was the answer to the bane of Western civilization for over three centuries, slavery and the slave trade. Thus, the colony was to develop without participating in either slavery or the slave trade. In essence, as British abolitionist policy evolved, legitimate commerce, that is, trade in items like cow hides, gold, beeswax, and cattle was to be developed in return for European, primarily British manufactures, like cotton cloth, liquor, guns, ammunition, or trinkets.

This trade, it was expected, would contribute to the emergence of a thriving African (Creole) mercantile class, a sort of African bourgeoisie similar to the British middle class. To ensure this, Christianity was introduced early in the colony through the efforts of the Church Missionary Society (C.M.S.), which started work in the colony in 1804. The C.M.S. not only succeeded—as indeed other missionary societies did as the nineteenth century wore on— making converts of the overwhelming portion of the population, but also introduced education. Many Creoles acquired a tolerable degree of education in missionary schools, which opened to them the world of business, politics, and culture 13.

Nevertheless, as has been indicated, the area of the colony in which agriculture did not thrive very well was extremely small. The economic base indispensable for the evolution and maintenance of Victorian Africans could be developed only if the trading patterns, and more often than not, the political relationship of the neighboring indigenous peoples both near and far were radically altered to serve the interests of the colony 14. In essence, it meant tighter relations with peoples like the Temne, Sherbro, Mende, and further inland, the Foulah or Mandinka. Indeed, the colony had no choice in the matter, if it was to exist at all. Thus, one important theme in the history of Sierra Leone in the nineteenth century was the enduring effort on the part of the colony to extend its formal and informal influence over the peoples inhabiting the interior.

The Western Sudan, an amorphous area that stretched from the Senegal-Guinea littoral to as far as sections of Northern Nigeria, figured prominently in the efforts of the colony to develop useful commercial relations with the interior. This was the land from which Mandinka, Foulah, or Bambara traders came with profitable commodities like gold, cattle, and hides, commodities so vital to the economic prosperity of the colony. One kingdom in this region with which the colony was quite familiar, and with which diplomatic and commercial relations had been early established, was Fouta Jallon, one of the leading Fulbe kingdoms in the Western Sudan 15.

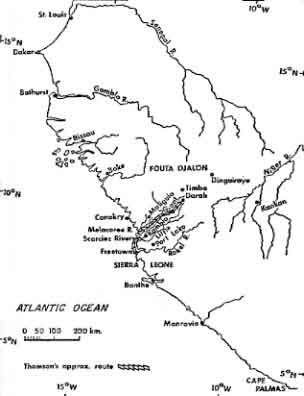

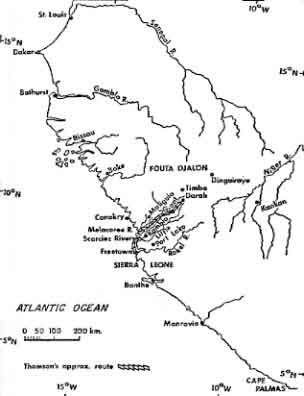

The decision to send an expedition led by William Cooper Thomson in 1841 from Freetown, the capital of the colony, to Timbo, the capital of Fouta Jallon, was therefore not surprising. The timing, organization, and goals of the expedition, however, make it rather outstanding, not only in terms of the history of Sierra Leone, but in the larger context of British policies toward West Africa. It bore the unmistakable imprint of Buxtonianism.

The decision to send a mission to Timbo was in large part a response by the colonial government to the persistent and strident pleas Principally from merchants, African, Afro-West Indian, and European, in the colony whose prosperity depended so much on the uninterrupted flow of commerce back and forth with the interior. Their major concern was the disruption that hampered trade following frequent and seemingly interminable disputes within and between the different African polities that stretched across the major trade routes. They had been encouraged by the forward and aggressive policies of Governors Campbell and Jeremie, who attempted to bring some of the major polities in the north into binding treaty relationships with the colony 16. This Buxtonian approach proved to be inadequate as trouble continued in the interior and injured trade. Hence the constant pleas of the merchants to the government of Freetown to send an expedition directly to Timbo.

Some time in the middle of 1841, a group of colony merchants petitioned the governor's council to send a mission to Timbo and the council acceded 17. The petitioners first applauded Governor Jeremie's accomplishment and then asked for the entire support of the government in undertaking the mission. They included Thomas Carew, John Miller, J. Weston on behalf of his brother H. Weston, John Fullerton on behalf of Charles Heddle (a very successful Eurafrican groundnut merchant with extensive interest in the northern rivers), R. Lawrence of Ridd and Dawson, I. R. Kidd, George Spilsbury, I. Campbell, John Ezzidio (a successful merchant and the first Sierra Leonean to sit in the Legislative Council), Isaac Pratt, successful trader and prominent citizen ("pillar of the United Free Methodists," in the words of Fyfe), W. H. Pratt (also an extremely successful African merchant), as well as 1. and W. H. Wise, who too were successful African merchants. Afro-West Indians included George Randall, Richard Fisher, and Edward Lemon on 'behalf of his brother A. Lemon.

The tardiness of administration in the colony, a principal factor of which was the frequent change of governors, and the perennial parsimony of Britain in extending commitments to African peoples during this era militated against speedy action. Between June and December of 1841, however, local merchants-liberated Africans, and Afro-West Indians taking the lead-generated enough enthusiasm for theproject in the colony to eventually pressure the government to provide money toward a partial defrayment of the costs of the expedition 18. Prominent settlers and liberated Africans like William Cole, William Jenkins, S. Lemon, and J. F. Pelegrin were now firm supporters of the mission. Another very important partici. pant in the advocacy of the mission was William Fergusson, an Afro-West Indian. It was important because Fergusson became acting-governor at the end of 1841, and it is no surprising coincidence that the Thomson mission left in December of 1841.

At a meeting of the merchants chaired by Fergusson in November, it was affirmed that Religion and commerce were the surest basis of civilization and here was an opportunity for the furtherance of both.

It was moved by William Cole, Esq. and seconded by Richard Lawrence, Esq., that it was important alike to the welfare of this colony and the cause of African civilization that there should be a more extended intercourse betwixt this colony and the Foulah country that a subscription be forthwith raised in aid of the colonial grant of £200 to defray the expense of a mission to Teembo [Timbo]....

J.F. Pelegrin and S. Lemon, who were also present, supported the motion, and it was carried unanimously 19.

Apparently at this same meeting, the leader of the projected mission, William Cooper Thomson, was selected. Later that month, Lieutenant-Govemor Fergusson properly communicated with Reverend Warburton, bishop of the C.M.S. in Sierra Leone, for whom Thomson had been working indicating their choice, explaining the purposes of the mission and soliciting his release from mission work within Sierra Leone. He noted that £400 had been collected towards the cost of the mission. He furthermore noted that Mr. William Cooper Thomson of the Church Missionary Society is a gentleman in whose talents, discretion and general ability to conduct the Embassy, this meeting has entire confidence. And that the lieutenant Governor be requested to make an application to the Local Committee of that Society, expressive of its desire, that the Committee would be pleased to appoint Mr. Thomson for the conduct of the Mission.

As to the purposes of the mission, he wrote,

So far, the objects of the meeting are of a nature, purely secular, but you will perceive that it was also considered desirable that the opportunity afforded by the projected Embassy, should not be lost, of rendering it, in so far as possible, subservient to other and more enlarged views, viz the extension of Christianity and the purpose of civilization 20.

Reverend Warburton, on behalf of the C.M.S., gave him consent 21. Truly, the aims, aspirations, and sentiments of the promoters of the Thomson mission could not have been more Buxtonian.

Before proceeding with the course of the mission itself, the identity of William Cooper Thomson must be examined. Such examination of Thomson's character and background is important since so much in terms of the outcome of the mission was to depend on his personal qualities. After all, in the words of the merchant gentlemen of the committee that had selected him, he was a man in “whose talents, discretion, and general ability” they had confidence.

William Cooper Thomson was most probably a Scotsman who arrived in Sierra Leone sometime in 1837 and took appointment with the C.M.S. as a linguist 22. He was first appointed to Yongroo in Bullom just north of the settlement at Freetown. Then he was transferred to Tombo Island near Koya where he stayed for a while, before returning to Freetown, where he was stationed at Kissy 23. In 1841, he joined Reverend Schlenker at Port Loko, an important Temne town in northern Sierra Leone, where the C.M.S. had just opened a mission 24. Thomson and Schlenker never appeared to have gotten alon g well, as the correspondence of both reveal, and by the end of the year he was about to be recalled to Freetown when he was offered the leadership of the mission to Timbo.

During this period Thomson had therefore spent most of his time predominently among the Temne and to some extent the Bullom. He was expected to master the Temne language, which he apparently did. He also claimed to have translated portions of the Bible into Temne and also worked on a Temne-English dictionary. When required to produce copies of his work, however, he failed to do it 25.

That he was a dedicated missionary cannot be doubted, but he tended to be over-zealous in the propagation of the gospel or in his crusade against slavery and the slave trade. For example, in June, 1840, a Temne woman and her child fled to Tombo Island British territory, where Thomson was stationed, but they were recaptured and forcibly taken back to Rokel, from which they had fled. Thomson appealed to Freetown to secure their release, an embarrassment for the colony since it had no jurisdiction in the neighboring territories, for example, Rokel 26. Nothing immediately came of his appeal, but the episode underscored both Thomson's overzealousness and the dilemma faced by the colony in its efforts to extinguish slavery and slave trade in its vicinity.

Thomson's career in the service of the C.M.S. up to his departure for Timbo certainly does not reflect the trust and confidence expressed in him by the merchants in the colony. His ability as a translator or linguist was unproven, nor can it be said that he had been very discreet in his dealings with the Temne, for whom he apparently developed a fondness. What he appeared to have in abundAnce was zeal and the determination to venture out on his own without control from higher authority.

Having been selected, however, Thomson was given elaborate instructions for the conduct of the mission by Lieutenant Fergusson and also a letter for the Alimami or King of Timbo. First, the instructions. He was to find out which of the three main trade routes to Timbo was best and the political and geographical nature of each.

These routes followed (a) the Mellacourie, (b) the Scarcies, and (c) Port Loko 27. He was instructed to follow the Mellacourie route for his own mission and return via Port Loko. He was also to ascertain the major causes of conflict that interrupted trade in the region and cures for these conflicts. Furthermore, he was to examine the best means for the expansion of trade with the interior.

He was particularly advised to cultivate friendly relations with the kings of Mellacourie and Tambacca, respectively Alifa Sanko 'and Bokari Sori, whose influence was so vital for the conduct of trade from the interior to Freetown. Bokari Sori in particular was to be placated and promised back payments of stipends not paid to him since his signing of a treaty with Governor Campbell in 1837 28.

When he arrived at Timbo, he was to deliver the letter from the governor to the Alimami and presents, observing all formalities. “Your own discretion and good cause will be the best guide in your intercourse with the Alimamee, and keeping constantly and clearly before your management of the trust reposed in you will be such as to justify the subscribers, in their selection, and reflect much credit on yourself, 29 ” he was told.

Besides acquiring as much scientific and geographical information as possible during the course of his journey, he was advised,

In your communications, however, with such of the Native Princes and other influential chiefs as you may meet with on your route—you are on all convenient occasions, freely and unreservedly to stigmatize the slave trade as a practice alike impolitic-cruel as regards the persons sent away, and impolitic as regards themselves, and the productive resources of their country; abundant illustrations of either of which positions will readily occur to you.

Thomson was also instructed to explore the possibilides, for the spread of missionary influences among the Foulah. He was cautioned,

The conduct, however, of this part of your Embassy will require on your part the greatest care, the utmost circumspection, the exercise of the soundest discretion. While on the one hand, you are called on to lose no favorable opportunity for acquiring a knowledge of the moral aptitude, fitness and willingness of the natives of the country for the reception of the great truths of Christianity, yet on the other hand, the fact is not to be forgotten that in pursuit of that object you will have to deal with the prejudices of a race of the most bigoted Mohammedan men who from youth to adult age have been taught to regard the belief and practice of the doctrines of Islamism as the best modes of conduct, the surest passports to future bliss. It may, therefore, be well to regard this part of your work as being of a nature, purely exploratory and intended to amass a volume of facts for the consideration of our missionaries.

Thomson was to keep a daily journal of his activities, and treaties and other objects resulting from the mission were to be considered property of the government of Sierra Leone 30.

The letter to the Alimami from the governor expressed similar aims. Addressed “My good friend,” it stated,

My sovereign the Queen of England is desirous that an intimate and sincere friendship should always exist betwixt the king and the people of Foota Diallon [Jallon] and the Colony of Sierra Leone.

After introducing Thomson as agent of the government, it recalled the visit of Dr. O'Beirne to Timbo some twenty years before and the commercial advantages resulting from it. It also expressed concern for the frequent interruptions of trade between Fouta Jallon and the colony and pleaded for cooperation in reducing such conflicts. It noted further,

The Seracoolies, the people of Kang Kang and the people of Boory [Boure] bring down gold to Sierra Leone, by way of the Foulah country and the Foulah people also bring down cattle, all of which are readily purchased by our merchants; but the Foulah country produces coffee and Benny in abundance, and I wish you to know that these articles would be bought as readily here as they are in the Rio Nunez.

Any quantity of well cleaned cotton will also be readily purchased.

Concern for the abolition of both slavery and the slave trade amon the Foulah was also expressed:

The Queen of England is most desirous that the slave trade should cease. She is the friend of all black people and has spent much money in trying to prevent those being carried away from Africa as slaves to other countries where they are badly used, made to work hard and get no pay for what they do. Why should Africans be sent away to other countries, to do that work for other people which they can do just as well and more profitably themselves in their own country.

I beg you then to join with the Queen of England in putting stop to the slave trade, and in place of sending slaves to the coast, send more gold, more coffee, more cotton.

The letter ended by soliciting the Alimami to send three or four boys along with Thomson on his return to be educated free of charge In the colony by the government. The result would be that “when bye and bye they return to Foota they may be able to impart to their country people some of that knowledgein which whitemen so greatly excel. 31”

A brief summary of the instructions of the C.M.S. is appropriate. They were generally similar to those of the government although naturally emphasis was placed on the spread of Christianity.

So, however, it may be fully known that you are an agent of the C.M.S., we need scarcely remark how important it will be to the cause of Religion, that you should in all things appear as Christian among these poor benighted Mohamedans and Heathen. We particularly feel this with regard to the Sabbath.

Thomson was also required to keep a separate journal for the C.M.S. He was to assess the receptivity of the Foulah to Christianity and to see whether Timbo could become a chief station for the spread of the gospel. Finally, he was to find out whether the knowledge of English was valued 32.

The concise examination of the instructions of the government to Thomson, the letter to the Alimami from the government, and the instructions from Reverend Warburton to Thomson reveal clearly the aims and aspirations of the promoters of the Thomson mission. The encouragement of legitimate commerce was the paramount goal. This development would, it was hoped, lead to the extinction of the slave trade. Finally, all this was to be accompanied by the spread of “civilzation” through the instrument of Christianity. In short, Buxtonianism was the real guiding philosophy of the promoters of Thomson's mission to Timbo in 1841.

All the practical arrangements having been made, including transportation, porters, interpreters, gifts, and so on, William Cooper Thomson left Freetown in December of 1841, arrived in the vicinity of Timbo at Darah in June of 1842, but remained trapped in Timbo until the second half of 1843 when he died 33. Thomson was accompanied by his son Billy (of whom he was extremely fond and who survived him in the journey), a Liberated African (Samuel Macauley from Wellington, a village in Freetown), a leading interpreter by the name of Sanassi, and several porters. They traveled first by boat from Freetown to Malaghea, a town on the Mellacourie, and thereafter by land to Futa Jallon. All in all, the journey was adventurous, sometimes tedious, fraught with all sorts of political and physical uncertainties, and extremely taxing. Right from the start, upon his arrival at the Mellacourie, Thomson encountered the hostility of the principal chiefs, Alfa Sankong (Sankoh) and Mamba Mariama Lahai, both dedicated Muslims 34. Apparently they resented not only penetration of -the interior by Europeans from the colony, thus preserving their "middle-mee" role, but also the threat posed to the continuation of the slave trade by the spread of Christian influences. As Thomson himself revealed in a letter written from Kumbayah, chief town of Fallah in April, 1842,

This Alifa and Bamba Mariama Laih [Lahai] of Malegiyah have done everything short of violence to turn me back to the Colony with disgrace; and had not God graciously supported me and enabled me, like David, to strengthen myself in him, I should through intimidation have been compelled to abandon the enterprise 35.

He was, however, able to break the hostility and proceed with the journey but still with great difficulty. Some of his porters defected or tried to persuade him to return to the colony.

He pushed through Benna and apparently succeeded in establishing friendly relations with the king, Alimami Barah Fodeh. He also established friendly relations with the king of Fallah, Debilah Kambah, and another chief, Alimami Bakkari. This can be pre, sumed because Thomson claimed to have signed treaties with the chiefs in which they handed over title to their territory to the colony. The originals, according to Thomson in Arabic, were left, however, with these chiefs and he promised to send copies to the governor." Whether such signing occurred is hard to substantiate.

Still, however, before Thomson could reach Darah, the residence of the Alimami of Timbo, he encountered resistance, typical of the attitude of the Susu, Mandinka, or Foulah chiefs. He despaired of

… recommendation to me [him], to return to the colony, as all the chiefs had come to the decision that my passing through the country would spoil it, as no white man had ever found road from the sea to the interior and they feared to make me a precedent-the truth is that Alifa, and I am told all the waterside Mandigoes, fear the approach of a European to the interior, or the mere circumstance of his visiting the countries behind Melachorie, and Benna above all where they have from time immemorial enjoyed a monopoly of the trade, and till this day are received by the natives as Foorote or Europeans and rule and manage them as they please, just as they formerly did the Temnehs 37.

By June, when he reached Darah, he expressed some optimism with regard to the acceptance of Western education by chief Debilah Kamba, who was willing to send his children to the colony. He also opened correspondence with the King of Tambacca. But he lamented the attitude of the Foulah noting, “What I regret is a vain desire on their part to identify the Christian religion with their own 38.”

The king of Timbo, Abu Bakr, was cordial in his treatment of Thomson, but apparently other important Foulah chiefs were not only hostile to Thomson, but even Abu Bakr himself for his reception of Thomson, and his seeming inclination toward reducing the slave trade. Thomson observed,

With a few, a very few exceptions, namely the Imam himself and the great chiefs of his own family, they care nothing but what will for the moment gratify their cupidity. As for the future prosperity of Foulah from a friendly connection with the colony and the surrounding nations, by the opening of the roads and the pursuits of commerce, except their old and favorite trade in slaves, they seem to be utterly indifferent.

It is a favorite maxim with them, that a Kafir's war gives them slaves and slaves give them money.

He also noted that prior to the civil war. which had politically distracted the Foulah for over fifty years, they received great tribute from the surroundin(y peoples as far as the Gambia 39.

The Foulah political structure was diffuse, requiring the consent of many clan leaders, who together with the Imam, decided on important issues of state. Naturally it was extre mely difficult for these leaders to arrive at decisions because of interclan rivalry. This state frequently resulted in civil war 40. Moreover, such a state tended to make the process of decision making slow and aggravating. Abu Bakr, the Imam, was unable to secure the agreement of the various clan leaders regarding Thomson's requests. They gave all kinds of reasons for not getting together, which Thomson found hard to believe. He suspected it was because he had not distributed enough presents to them 41.

More likely than not, the Imam failed to win the cooperation of other Foulah leaders because of their resentment of him as well as Thomson and his intentions. The worthy, valiant, but overzealous crusading action of Thomson in securing the release of an enslaved Liberated African from the colony, George Cooper, may certainly have injured his cause 42. Cooper, who grew up in Wellington, had been sold into slavery in Timbo, converted to Islam, spoke the Foulah language, and to all intents and purposes had been absorbed into Foulah culture. Nevertheless Thomson negotiated for his release, an action reminiscent of his antislavery activities on Tombo Island in the colony.

The Foulah leaders also claimed that Thomson's visit occurred at an inappropriate time. They were working hard to cultivate their farms, which had suffered as a result of the devastation of four successive years of locust plagues 43. Although this was certainly a factor, it also served as a convenient excuse. The plain truth is that the Foulah leaders generally resented Thomson's presence.

Adopting what might be termed “the politics of procrastination,” the Foulah leaders did not ask Thomson to return to the colony, but kept holding promises out to him. They were far from forthright. Thus, Thomson kept waiting, not recognizing that he had been trapped. He could not return to the colony without the goodwill of the Foulah and other intervening chiefs along the path to the coast and also without accomplishing his objectives, which he could not do without the cooperation of the Foulah leaders. The choice, if indeed there was one, was cruel.

To compound the situation, Thomson's most cooperative host, Abu Bakr, became the victim of a coup in May 1843 and fell from power. The new Imam Omar, son of a former Alimami or Imam who had established relations with the colony in the 1820s, was hostile to Thomson. Thomson's feelings were expressed in one of Ins letters: “The just and merciful Abu Bakr has been deposed and the sanguinary Omar is now master of Foutah Jalloh 44.”

Thomson began to feel the strain of his undertaking. His letters rieflected a sense of resignation and futility. He realized by October of that year that he had been the victim of a hoax, that he had indeed been a prisoner. All this combined to cause his death in November. It was reported by his son Billy, who survived him and returned to the colony 45. Thus ended the mission to Timbo, a tragic end to an optimistic start. Although the end has overshadowed all assessments of the Timbo mission by Thomson, it, however, represents a distorted picture. In my opinion, a fair assessment of the mission should involve not only Thomson's failure, but also its inspiration and the mere fact that it was undertaken at all. Whether the mission failed because of Thomson's personal inability or the hostility of the Foulah and other peoples is open to question. I am iuclined to believe that both factors contributed to it.

In terms of providing new information, political, economic, or geographic,, Thomson's mission confirmed what was already known. For example, he noted the produce that was traded in the Mellacourie region. These included slaves, rice, groundmits, cattle, hides, wax (beeswax), gum, and kola nuts. This was something that the colony was already aware of. Thomson, however, added the potential for cotton growing, a commodity no doubt attractive to the colony 46.

The extent of the slave trade was also confirmed. Slaves were being shipped in large numbers to the northern rivers where the Portuguese and Spaniards appeared to be the principal buyers and carriers. Kakony was identified as the principal port of trade 47.

Since the treaties that Thomson claimed he had signed with some chiefs were never located, and since he had failed to secure any purely formal political agreements with the Alimami or Imam, the colony had gained little or nothing. But the visit underscored the interest of the colony in Fouta Jallon, and this could not have been lost on Foulah leaders.

Significant contacts were not established with the chieftains of other important areas of commerce, for example Segu. Thomson claimed to have won permission to visit Segu, but since he never made the visit, this could be discounted. He encountered, however, one Sheriff Hamidu Fallah from Segu, who was apparently impressed with an Arabic Bible donated to him by Thomson. Hamidu Falah, an influential and powerful Moor probably a successful trader as well, was making a trip to Freetown, and Thomson gave him a letter of introduction to Reverend J. Warburton 48.

With regard to the spread of Christianity, the reports of Thomson were not encouraging. Islam was very strong in the region and the enthusiasm for accepting Christianity displayed by some rulers represented no more than verbal professions. His visit, therefore, was never followed up by any Christian mission among the Foulah.

Yet these failures do not make the Thomson mission insignificant. The inspiration of the mission, Buxtonianism, came more from African and Afro-West Indian residents, settlers, and Liberated Africans than the British government. The partnership between government and business was not entirely between Europeans, as was the case of the Niger Expedition of 1841, but between Europeans and Africans, with Africans taking the initiative. Insofar as their goals involved an extension of “the blessings of civilization” to eradicate slavery and the slave trade, they thus confirmed the hope of abolitionists in England that, given the opportunity, Africans would indeed develop and practice values recognized as “civilised.”

The failures of the Timbo mission did not mean an end to contact with the Foulah. Since they themselves were interested in commerce, in subsequent years Freetown's commercial relations with.the Western Sudan continued to expand. Finally, in 1873 direct contact was again established in Timbo by Edward Blyden as emissary from the colony 48. Nor did Buxtonianism as a philosophy die among British officials and colony residents in succeeding years. Legitimate commerce wasencouraged while the slave trade was attacked and ultimately destroyed. Efforts to spread the gospel were undertaken, though feebly, in the northern interior of Sierra Leone. The acceptance Of Victorian values by African residents of the colony, Creoles, was tolerably successful. These values were carried beyond the colony to the interior, both north and south. yet, in the end, when colonW rule was imposed on the indigenous peoples in the interior by the French and British at the end of the nineteenth century, it mustbe admitted that Buxtonianism was unwittingly a contributory factor toward such a development.

Notes

1. For a useful account see C. W. Newbury, British Policy towards West Africa (London, 1965).

2. Studies dealing with the history of the abolitionist movement include Reginald Coupland, The British Anti-Slavery Movement (London, 1964); Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery (London, 1964); P. D. Curtin, The Image of Africa: British Ideas and Action 1780-1850 (Madison, Wisc., 1964); L. Griggs, Thomas Clarkson: The Friends of Slaves (London, 1936); Christopher Fyfe, History of Sierra Leone (London, 1968); and John Peterson, Province of Freedom (Evanston, Ill., 1970).

3. T. Fowell Buxton, The African Slave Trade and Its Remedy (London, 1840), p. 15. This estimate, regarded as exaggerated and unreliable, has been revised downward by P. D. Curtin. See his Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census (Madison, Wisc., 1969), especially chap. 8.

4. For a good study of the antislavery squadron, see Christopher Lloyd, The Navy and the Slave Trade (London, 1968). Also, H. W. H. Pearsall, “Sierra Leone and the Suppression of the Slave Trade,” Sierra Leone Studies n.s., no. 12 (December 1959): 211-29.

5. Frequently in the 1820s, this took the form of attacks by West Indian interests on the colony of Sierra Leone, symbol of abolitionism. One such example was the publication of an article unfavorable to Sierra Leone by a Mr. McQueen that brought a strong defense from Kenneth Macauley in his Colony of Sierra Leone Vindicated (London, 1968).

6. J. Callagher, “Fowell Buxton and the New African Policy, 1838-1842,” Cambridge Historical Journal 11 (1950): 36-58.

7. Buxton, African Slave Trade, p. 273.

8. Ibid., p. 513.

9. It took the form of sponsoring the so-called Niger Expedition of 1841. See C. C. Ifemesia, “The ‘Civilizing’ Mission of 1841,” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 2, no. 3 (1962); J. F. Ade. Ajayi, Christian Missions in Nigeria 1841-91 (London, 1965), pp. 10-13.

10. Recently, a historian specializing in West Indian history produced an appropriate corrective comment calling for a better understanding of West Indian history by historians specializing in Africa, in order to avoid inaccurate conclusions. Using the historiography of the 1841 Niger Expedition as a case study, he attributed British policies more to matters relating to the West Indies than the “visionary” (his word) proposals of the Buxtonians. Unfortunately, while attempting to correct an error. he committed a similar one, since no one familiar with West African history could have claimed that British acceptance of Buxtonian proposals was based solely on “fanciful” schemes. The material prospect was tan indispensable Ingredient. See W. Green, “The West Indies and British Wes African Policy in the Nineteenth Century: A Corrective Comment,” Journal of African History 15, no. 2 (1974): 247-60.

11. For the early history of the colony, see, Peterson, Province, especially chaps, 1-3; and Fyfe, History, chaps. 1-7.

12. R. Clarke, Sierra Leone: A Natural History of the Colony (London, 1843), p. 68.

13. For a detailed elaboration of the development of Creole society, see Peterson, Province; and Arthur T. Porter, Creoledom: A Study of the Development of Freetown Society (London, 1966).

14. See E. A. Ijagbemi, “The Rokel River and the Development of Inland Trade in Sierra Leone,” Odu n.s., no. 3 (April 1970): 45-70; and “The Freetown Colony and the Development of ‘Legitimate’ Commerce in the Adjoining Territories,” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 5, no. 2 (June 1970): 243-57. For a detailed study of indigenous trading patterns and developments in the nineteenth century, see A. Howard, “Big Men, Traders, and Chiefs: Power, Commerce and Spatial Change in the Sierra Leone-Guinea Plain, 1865-1895” (Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin, 1972); and for the interaction between trade and politics, particularly colonial intervention, Gustav Deveneaux, “The Political and Social Impact of the Colony in Northern Sierra Leone” (Ph.D. diss., Boston University, 1973).

15. The colony sent a mission to Timbo in 1794. Fyfe, History, p. 57. Another mission jed by Dr. O'Beirne visited Timbo in 1824 that was reciprocated by the Foulah, see Acting Governor Hamilton to Bathurst, April 21, 1824, CO 267/60, Public Records Office, Great Britain.

16. Deveneaux G., “Northern Sierra Leone,” pp. 125-30.

17. MacDonald to Carr, 5 August 1841, petition enclosed in dispatch, CO 267/165.

18. Fergusson to Stanley, 31 December 1841, CO 267/166. See also 1, 2, and 5 of same dispatch for details on contributions of merchants. Also, Fyfe, History, p. 222.

19. Minutes of Meeting of Merchants and Others, 13 November 1841, C.M.S. CAI/M10.

20. Lieutenant Governor to Reverend J. Warburton., 22 November 184 1, C.M.S. CAI/M10.

21. Reverend 1. Warburton to the Lieutenant Governor, 25 November 1841, C.M.S. CAI/M10.

22. Surgeon Furgusson's Certificate respecting Mrs. Thomson's Health, 8 March 1839, C.M.S. CAI/M8. Thomson himself implied Scottish nationality in a report to Lord Stanley in the following words, “Being a native of a mountainous country I was desirous of measuring my powers, with the steep roads of Africa. Though I still carried the box containing the chronometer, I have not yet felt what in Scotland, I should have called fatigue.” Lord Stanley, “Narrative of William Cooper Thomson's Journal from Sierra Leone to Timbo, Capital of Futah Jallo, in Western Africa,” Journal of the Royal Geographical Society 17 (1846): 115. Fyfe correctly accepted his Scottish nationality. Fyfe, History, p. 214. The claims by Hair that he was English are therefore erroneous. P.E.H. Hair, “Notes on the Early Study of Some West African Languages: Susu, Bullom, Temne, Mende, Vai and Yoruba,” Bulletin IFAN, 23, no. 3-4 (Series B) (July-October 1961): 683-95. Similarly, the extravagant claim by Butt-Thompson that Thomson was an African who landed in the colony in 1824 should be entirely dismissed, F. W. Butt-Thompson, Sierra Leone in History and Tradition (London, 1926), p. 22.

23. Thomson's Report Kissy, 22 September 1840, C.M.S. CAI/M9.

24.Thomson to Reverend J. Warburton, 20 May 1841, ibid.

25.Warburton to Thomson, 29 June 1841, ibid. Also, Hair, in “Notes”, who claims that none of the alleged translations have been located.

26. Minutes of Council, 17 June 1840, CO 270/21; and C. C. Miller to W. C. Thomson, Esq., 18 June 1840, CO 269/13.

27. Lieutenant Governor Fergusson's Instructions to Mr. W. C. Thomson, 18 December 1841, C.M.S. CAI/M10. They are also to be found in Fergusson to Stanley, 31 December 1841, enclosure 7, CO 267/166.

28. “Ferguson's Instruction,” C.M.S. CAI/M10.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid.

31. Lieutenant-Governor Fergusson to Alimamee Yah Yah, King of Teembo, 18 December 1841, C.M.S. CAI/M10.

32. Reverend J. Warburton to W. C. Thomson, Esq., 13 December 1841, C.M.S. CAI/M10.

33. Fyfe, History, p. 222. C. P. Groves, The Planting of Christianity in Africa, 4 vols. (London, 1954), 2:46.

34. Thomson to McCormack, Esq., Kambayah, Chieftown of Fallah (tributary of Footah), 16 April 1842, C.M.S. CAI/M10.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.

37. Ibid.

38. Thomson to Warburton, The Country Residence of the Iman, Darah, near Teembo, 18 June 1842, C.M.S. CAI/M10.

39. Thomson to Warburton, Darah, 19 January 1843, C.M.S. CAI/M10.

40. For a discussion of this problem, see, Jean Suret-Canale, “The Fouta-Jallon Chieftaincy” in West African Chiefs, ed. Michael Crowder and Obaro Ikime (New York, 1970). pp. 79-97.

41. Thomson to Warburton, Darah, 19 January 1843, C.M.S. CAI/M10.

42. Ibid.

43. Thomson to Warburton, Darah, 22 July 1842, C.M.S. CAI/0214.

44. Thomson to Warburton, Darah, 20 May 1843, C.M.S. CAI/0214.

45. Lord Stanley, “Narrative of Mr. William Cooper Thomson's Journey” p. 107.

46. Ibid., pp. 110-11.

47. Thomson to Warburton, Darah, 21 October 1843, C.M.S. CAI/0214.

48. Thomson to Warburton, Darah, 22 March 1843, C.M.S. CAI/M.10