Katharina Lobeck

“The Nyamakala of Fouta-Djalon”

An interview with Banning Eyre

Katharina Lobeck |

|

Banning Eyre: Your work focuses on the Fouta-Djalon in Guinea. Tell us about that area.

Katharina Lobeck: The Fouta-Djallon used to be home to a Fulɓe theocracy in the past. It was an Islamic empire, very strong, very powerful, and a lot of that heritage is still felt up to these days. I've been working with quite a range of people from artists who live in villages, from girls who entertain themselves just singing and clapping, to very local musicians who play at weddings, naming ceremonies and so on and so forth, up to modern artists who try to chose more modern production for their traditional music. They have actually been quite successful with it, not internationally yet, but we hope that will change,

B.E.: Let's start with the village music. Tell us about a great traditional musician you worked with.

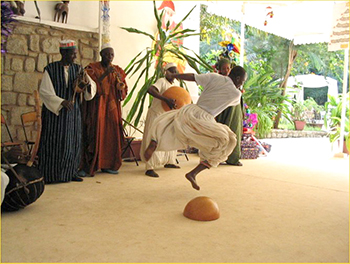

K.L.: Mamadou Mamou is a singer from Lobe. He's not actually the greatest singer, but he works with the greatest flautists in the entire region, who ended up being my teacher. His name is Sory Maci. The band of Mamadou Mamou features the bass harp (bolon), and the flute (serdu), various flutes, which are the most typical Fula instruments, as well as castanets (laala) and the calabash (horde), which you tap with metal rings (kurunda). The players put ten metal rings on their fingers and it makes this beautiful rattling sound. They tend to go round to weddings and naming ceremonies and play their music and dance in an extremely captivating, acrobatic style. They are very spectacular and flamboyant—quite impressive.

B.E.: Is there an older, ceremonial basis for this wedding music?

K.L.: I think this music has always been performed for life rites, especially weddings and circumcisions. But there is also one particular context which it is most famous for, which is called hirde, and those are evening gatherings, during which the entire village gathers, or especially young people gather, and listen to the musicians or bands. There used to be two particular forms. One was a sitting gathering, jooɗoo hiira. The other was a standing up gathering. They had two particular kinds of music. Now the sitting one is very, very quiet. The instruments that would be played were lutes that were struck, and the whole atmosphere would have been very quiet and relaxed. The standing ceremony is called daaro hiira, and these were more invitations to dance, so the instruments would be drums, djembe, and the flutes. Those kinds of celebrations gave the people in the village a context during which they could gather and have a good time and enjoy themselves.

Daaro hiira would have been the most typical context for the flute music, not at all the jooɗoo hiira. Because as well as two different sorts of music, you also get two different social categories. Thee musicians of the daroo hiira would have been mainly coming from the slave status, whereas the musicians of the jooɗoo hiira would have been nobles. So there's a very distinct social difference between the two events. The standing instruments were much more associated with excitement and dancing and were considered more appropriate for people of lower social status. I suppose it's a little bit like the difference between a rock concert and a classical music concert.

B.E.: How far back do these hiirde ceremonies go in Fula history?

K.L.: This particular type I think is distinctive to the Fouta-Djallon, and it resulted from the whole history of the region and the social hierarchy of the theocracy. But the Fulɓe people are spread out all over West Africa. You find Fulɓe communities in Senegal, in Mali, Nigeria, Niger, all the way to Cameroon. And wherever they went, they developed very distinct cultural practices, and their musical practices are also quite different from place to place.

B.E.: The pentatonic flutes seem to be found in a lot of Fula communities.

K.L.: The Fouta-Djallon one is not actually pentatonic [five-notes scale], but it's the one where they sing and play at the same time, so you intersperse sung notes with played notes and people make a lot of fun with it. They call it gimmicks themselves. “Oh yeah, the Fulas, they know how to do all the best gimmicks on the flute.” But the flutes are very typical for the Fula people in general. One of the reasons is that the Fula were traditionally nomadic cattle herders, and I think all over the world you have this phenomenon where flutes tend to be the favorite instrument of shepherds. They are fairly easy to make. They are light to carry. So the Fulas being cattle herders, they are very much associated with flute music.

Now the particular type of flute is different from region to region. So people develop different styles of playing flutes and making them. What's particular about the flute tradition in the Fouta-Djallon is the singing and playing at the same time. It's very powerful if you listen to that flute. It didn't leave me alone after the first time I heard it. I'm finding myself now writing a PhD on it. It's very powerful and very loud, and very, very beautifully ornamented. In the Fouta-Djallon, the flute is actually heptatonic [seven-notes scale], whereas in other regions, the Fulɓe tend to play more pentatonic music. Like if you listen to Fulɓe music from Niger, you can hear much more of a pentatonic sound, which relates to the style of Ali Farka Toure.

One of the people who are actually very interesting are Omar Ka & the Fula Band. They are based in Holland now, and Omar is originally from Senegal, but his mother came from Niger. Now, the Fulɓe from Senegal play music very much like we have heard from Baaba Maal, very strong griot style. Now when I put on Omar's CD, I just realized it was completely different and I thought, he must be coming from Niger and I phoned up and he said, "Yeah, my mom comes from Niger." So you can identify different origins. But it is still related at the same time. It's a bit like the language. The Pulaar language is spoken in different dialects in different regions. So Fulɓe from different regions might take a little bit of time to really come to a complete understanding of their mutual dialects.

B.E.: Tell us about some more of the more traditional musicians that especially impressed you in Guinea.

K.L.: One artist who people are constantly talking about to me is a guitarist and singer called Bah Sadio. I suppose you would call him a modern artist. He's supposed to be the first modern artist of Fulɓe music. He was forced into exile under the regime of Sekou Touré, who hit out quite strongly against the Fulɓe communities of Guinea. So he went to France and recorded an album there, and he tragically died of alcoholism in exile. His music is extremely powerful in its presentation. People even from the very young generation can still relate to that music. He wrote two very famous songs. One translates, “One Day I will Also Come Back to My Place.” It was a very strong message of yearning to be able to go back home and it became immediately popular with the Fulɓe expatriates in France, in Senegal, in Sierra Leone, and so on. The other track that has become very popular is called Jeere-leele, which evokes a little bit of those gatherings I was talking about earlier. He talks about playing in the moonlight. I think it's a very important element of Fulɓe culture.

Bah Sadio is a fabulous singer. He studied also with one of the most important artists of Fulɓe music, which is El Hadj Moƴƴere. He's very old now. I think he's coming up to his 90s. He's got a very unique style of singing, a very free style, very much spoken word, but the words he says are so meaningful and so deep that people can just sit glued to their transistor radios and try to find out what he was talking about. Being a very old man now, he has seen a lot of changes in the history of Fulɓe music in Guinea. He was recorded before independence, and assumed a reputation for ridiculing people in public, humiliating people, which was very much a feature of the nyamakala, the Fula artists.

B.E.: That word nyamakala also describes a professional class among the Manding people, including griots. Does the word mean the same thing here?

K.L.: Well, that's a slightly confusing aspect. It means a very different thing for the Fulɓe. nyamakala is a Maninka word which refers to the class of artisans, including griots, blacksmiths, and so on. Now in a Pulaar context, the word has taken on a different meaning, and it refers to this class of musicians who were primarily found among the slave community, not exclusively, but primarily. So of very low social status, and treated with a lot of suspicion and very much associated with sorcery, and also with their ability of harming people, and their insolent speech. People tend to be quite scared of the nyamakala. People would always warn me that I shouldn't be hanging out with them too much. Now all those people who play those beautiful instruments like the Fula flute, and the djembe, the calabash, they are all part of the nyamakala. But the important difference is that in Guinea, for the Fulɓe, nyamakala is an artist who has decided to become an artist himself. He is not born an artist. And people usually struggle very hard to become musicians. Quite often it involves running away from home, breaking with your entire family, and risking a whole lot of things to actually become a musician.

It could be a family of a former slave; it could be the family of a griot; it could be the family of a blacksmith; it could be the family of a noble. At some point in their lives, they have made this decision to follow the nyamakala and to earn their life by making music.

B.E.: Once you make that decision, what do you have to do?

K.L.: It's very different from the Mande context. The Mande griots are very much associated with singing people's genealogies, the history of the empires, the histories of kings, praise songs. Now the Fulɓe nyamakala also sing peoples praises, but in a very different way. It depends much more on the context. You might have a hiirde, one of those evening gatherings. Somebody might give you some money and you will sing his name. You might sing his friend's name. But you will not sing his whole geneology. The Fulɓe nyamakala don't generally do this. They might just sing, “Oh, thank you, Mr Diallo, for giving me 1000 Guinea francs, and I praise your wife and your beautiful children.” But they will not recite the entire geneology. This is the work of the griots.

B.E.: And where does the insulting come in?

K.L.: It has to be said that those things don't exist so much any more, and the nyamakala do try very hard to get away from that history because it does link them to a low social status, and to an insolent nature, whereas the nyamakala today very much regard themselves as artists and want to be respected as modern artists. But still, there is this history, and I think that in the past it must have played a role of social justice in a way, because there is a saying in Pulaar that says that the only ones that the people fear are the chief and the nyamakala, and the only one that the chief fears is the nyamakala, because he will tell you straight to your face where you are going wrong, and why, and he will not do it in any polite way whatsoever. But apart from this, there has also been a lot of association with just humiliation in order to gain money.

B.E.: People pay money to avoid being humiliated?

K.L.: Exactly. If you meet with a nyamakala, and he asks you for money, or even more for food, and you refuse him to give it to him, then you risk “A” being harmed by his sorcery skills, and “B” being humiliated in public because it is stingy to refuse food to a poor person. So it's risky for you and generally not a good thing. But as I said, those things only exist in their rudiments now.

B.E.: So what do modern nyamakala sing about?

K.L.: Fulɓe songs tend to be very sentimental and romantic. There's a long history of love songs. One of the songs that illustrates this best is this song called Ɓulun Njuuri by a very famous nyamakala singer called Binta Laali. She now calls herself a modern artist because she has now released a few cassettes. She is a very old, very dignified lady who has been around ever since the first days of independence. And Ɓulun Njuuri means “the source of honey” and it talks about spending a night with your darling, and she very poetically illustrates the whole situation and includes Pulaar proverbs, very profound proverbs, in it, and it's a very beautiful, very sentimental song. This version was recorded two years ago, but it goes back to an older song. She keeps reworking older songs. She's in her 60s now.

B.E.: Tell us about some of the Fula pop singers today.

K.L.: One who really caught my attention when I first went to Guinea is a young singer called Lama Sidibe. Lama is interesting because he doesn't come out of the nyamakala tradition. He also decided at some point to become a musician, but he decided to study actually with the Manding griots, so his first local cassette was very much in a Mande style, and then Pulaar music suddenly became very popular in Guinea, so he did research on his own tradition in a way, and came out with a beautiful record called Falaama. One of the most outstanding tracks I think on there is a track called Mamou, which he sings in praise of his home town, and you can hear very much traditional elements in there, such as the calabash shakers, the triplet rhythm which is really typical of Pulaar music in Guinea. And the flute. The flute is always the distinctive element of all Pulaar music that is being released in Guinea. All the Fulɓe artists have got a flute in there, and Lama Sidibe, his real strength is that he has got a very powerful, persuasive voice.

Another singer who has just released this year is a blind singer called Mama Yergue Barry, who once again has a very powerful voice. If you hear him singing next to you, it just blows you away. You kind of take three paces back. He also plays the calabash called horde. His album has just been immediately appreciated by mainly the Fulɓe community but also the other communities. It's a very good production done in Abidjan, and again, you can hear this beautiful Fula flute. So what most of the modern performers do is use elements of the tradition without sticking too closely. One of the elements they always use is the flute. The second one would be the content of the songs in a way, the idea of romance and love. And some of the local rhythms. But then they also combine those rhythms with the rhythms of zouk and soukous, which are extremely popular in Guinea.

B.E.: I'm curious about what you said regarding Sekou Toure's aggressive actions against the Fula communities. What was that all about?

K.L.: I think one has to be careful talking about the Sekou Toure era as one era, because there were different phases. I do think that Sekou Toure tried to create a coherent sound of Guinean music, which would reflect Guinean pride and nationality, and would reflect a modern Africa. Now, he was Maninka himself, but I don't actually think that the fact that most music that was popularized under Sekou Toure is only because he was a Maninka. It's also due to the fact that the Mande people have this institution of griots, and the griots know history from the earliest days of the Malian empire. They are very much used to praising people, but also in a social role as political advisors and mediators. So they were in a perfect position to fulfill this role that Sekou Toure had been looking for to promote Guinean culture nationally and internationally, and create national unity. Now the Fulɓe artists at the time, singing more sentimental songs and love songs, wouldn't have served the same purpose. The fact that there was a lot of Maninka music during the first regime has very much to do with that.

[Note. Actually, throughout the centuries Fulɓe griots (sing. gawlo, plur. awluɓe) have built a similarly rich epic tradition, which mixes genealogical praise-singing, legendary heroes, and state historiography. In the early years of the republic of Guinea, Fulɓe griots — such as konni (luth) virtuoso soloist and narrator Farba Manma Niang — were celebrities regularly featured on radio. Thus, Farba Niang plays several songs on Guinea's first ever recorded albums: Sons nouveau d'une nation nouvelle. Edition spéciale, 1961. In one of them, Laguya, he celebrates the bravery of Fuuta-Tooro warriors; an indication that Fulɓe civilization never was bereft of the griot-type of art. To the contrary, this is a highly developed Pular genre, as Katharina herself acknowledges in reference to Baaba Maal's repertoire, which draws alternatively from nyamakala and awluɓe inspiration!

Master oral historian from Mamou, Farba Toura Seck was one of Niang's successors. And each Fuuta-Jalon region had its Awluɓe, some blending verbal and written communication, thanks to their advanced literacy in Pular ajami. Such personalities ranked at the top among Awluɓe and were called Farba.

See also my transcription of the Alfa Abdurahmani Koyin Epic (asko) performed by Farba Ibrahima Njaala and Farba Abbaasi.

Kèdo is the Mande version of Alfa Abdurahmani Koyin. Kouyate Sori Kandia recorded an excellent rendition of that song. One of the greatest griots of all times, Kandia was born and raised in Ditinn, Fuuta-Jalon. Natively fluent in Maninka and Pular, he was a bicultural Jeli Fuutanke.

Last, Katharina beautifully captures and sums up the genius of Hamidou Balde, alias Bonnere (The Bad) alias Moƴƴere (The Good), from the Diiwal (province) of Koyin (Tougue). But she does not mention the late Sori Boobo Diallo, the other super-nyamakala of the 1950s-1960s, who gave up his art (tuubugol) to became a muezzin at the mosque of his hometown of Koubia, then part of Labe.And D.W. Arnott notes that: « Where large-scale communities of mainly settled Fulani have been established under influential leaders, court singers have flourished under a system of patronage, similar to that of the neighbouring Mandinka, Bambara or Hausa. Their praise-songs often celebrated and glamourized the achievements of the chief and his predecessors, or recounted the deeds of ancient heroes. An outstanding example of such a poem is the traditional epic of Silaamaka and Puloori, as sung to his three-stringed lute by the famous “griot” (professional praise-singer) Boubacar Tinguidji. » — Tierno S. Bah]

Now, Sekou Toure's regime got increasingly paranoid the longer he stayed in power, and increasingly more oppressive. And he started lashing out against the Fulɓe communities around 1976 and after that. So that's kind of the second period, and most of the people who went into exile went after that time. And Fulɓe music wasn't really produced. There were a few artists, like the orchestras of Telemele, and Labe and Mamou, who play this beautiful Guinean orchestra sound, very much reminiscent of Bembeya Jazz and other orchestras. Coming out of Fula, but they would have been singing in Maninka as well as Pulaar. There were groups everywhere in Guinea. Every prefecture had a group, so Mamou, Labe, and Telemele are three of the most important regions in Fouta-Djallon. Each of those three towns would have had an orchestra attached to them. They never achieved the fame of Bembeya Jazz or other bands that were based in Conakry, but they did play an important role at the time as well.

What we hear now is modern Fula music, which includes artists such as Petit Yero, Lama Sidibe, Binta Laali Sow, Sekouba Fatako, who are extremely popular in Guinea now. They have only really started doing so-called modern music since about 1995, 1996. It's a very recent phenomenon. Sekou Toure's “First Republic” broke down in 1984 with his death. I suppose it took producers awhile to establish themselves and to take on artists who sounded quite different from what had existed before. So this explosion of Fulɓe artists has only started around the mid 90s.

B.E.: Once they did start releasing these Fula pop recordings, did the music catch on quickly?

K.L.: It was quite successful right from the start. The Fulɓe are the largest ethnic group in Guinea, so a lot of Fulɓe would have been pleased to be able buy a cassette sung in Pulaar, and hear their tradition modernized. At the same time, the appeal goes beyond the Fulɓe community because the sound of the modern music is very much alike whether you have a Maninka, Sousou, or Fulɓe artist. The production would be similar, and a lot of the beats that are used would be similar, which is one problem of Guinean production. But on the other side, it also means that whether you sing in Pulaar, Manika or Sousou, chances are that people from other ethnic groups might like your stuff as well.

Usually when you look at an album of a Pulaar artist like Binta Laali, she might put two songs that are more clearly rooted in her own tradition, and others that just fall very much into the so-called “variété” genre of popular Guinean music and use a zouk beat or a soukous beat and are very much accessible to everyone. I still think that artists mainly appeal to their own people because of the language. The message people transmit is very important, whether it's just praises, whether it's sentimental, whether it's historical, people like to listen to things sung in their own language. We all do.

B.E.: Well if the Fula are the largest ethnic group, I guess it's no surprise that their pop music would sell.

K.L.: It's not surprising at all, especially when you look at the producers who sit in Conakry and you realize that they are all Fulɓe. It's actually surprising that it has taken so long.

B.E.: Any other modern groups we should know about?

K.L.: One group that I would like to talk about is actually a rap group. It's called Kill Point. They are not exclusively Fulɓe—it's more mixed; they have got one Pulaar rapper—and as everywhere in Africa and all over the world, rap is one of the most popular genres now, especially among the youth. I was talking about the insolence of the nyamakala before. They actually dared to speak out against the system and the regime. They don't do this anymore. They take a much more moderate position. But now the rappers who come from a younger generation, actually take very much this social role of speaking their mind, possibly insulting, but definitely saying what they don't like. That's what the younger generation wants to hear; that's what they need to hear about. In Guinea, there are actually not many artists who dare speak out about the situation and politics. One of the people who have been among the first to do it, and the most successful are Kill Point. They rap in all the Guinean languages, in French and in English. None of the producers has decided to take them on. So what they did is to set up their own little company called Kill Point Productions, which is a very brave thing to do. It's very brave for a group of youngsters to try and break this network of existing producers in Guinea.

B.E.: So they actually criticize the government?

K.L.: Exactly. They've been doing it for quite awhile now. Their latest album has just come out this year. It's called Le Combat Continue. They're immensely popular in Conakry, among the young people of Conakry. Kill Point are, I suppose, kind of heroes I think among the young generation, and have inspired a lot of rappers to do a lot of things. It's the youth that follow them.

B.E.: Have they been harassed for that?

K.L.: I don't know, but I bet they have, because it's very very hard to say anything against the government in Guinea. It's a long tradition of oppression and there's a lot of mistrust that reigns. You can feel it in the whole society, that this country has been oppressed for a long time. It needs people like that who do speak out.

Fula Flute, among others, gives a taste of the richness of this instrument — T.S. Bah